Outlet: The Virginian-Pilot

©

WHEN SUFFOLK wins a new business, Virginia Beach benefits. And vice versa.

That premise underlies the principle of regional cooperation, on economic development or anything else. All the leaders of all the cities of Hampton Roads pledge at least notional allegiance to that cause.

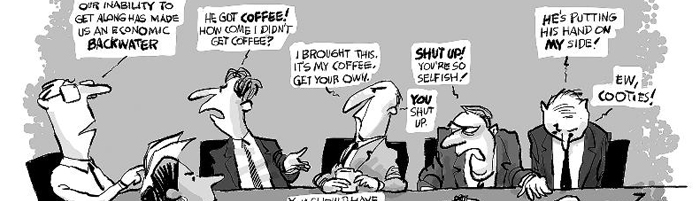

Their practice, however, is a different matter.

When Norfolk attempted to build an outlet mall on its side of the border with Virginia Beach, it turned into a pitched battle over competing economic interests, complete with aborted meetings and hard feelings.

When Portsmouth faced an existential crisis in rising new tolls at its border with Norfolk, the prospect – which has since proved devastating to the city’s commercial culture – was greeted with silence from its larger and richer neighbors.

When Suffolk wanted state money to increase capacity on a massively overburdened U.S. 58 – a critical east-west commercial and evacuation artery – the city simply burdened the road with more traffic, on the principle that the gridlock would attract cash that would otherwise go elsewhere.

None of this is new or surprising. Municipal leaders will always act in the best interest of voters or face their disapproval in the next election. For too long, those leaders have assumed that municipal interests stop at the border with the next city.

There’s been good reason. Parochialism is hardly the province of politicians alone. Plenty of people assume that the cities of Hampton Roads are in a constant state of competition with each other.

A new study sponsored by the Hampton Roads Economic Development Alliance shows that not only are the citizens of the region – and the cities’ economies – more interdependent than the behavior of politicians would indicate, that interdependence is growing.

“[I]t is commonplace for mayors, city council members, and economic development directors to act as if the only really good economic development project is the one that is located squarely inside their own city or county,” reported Vinod Agarwal and James V. Koch, economists at the Strome College of Business at Old Dominion University. “However, in previous studies for the Hampton Roads Economic Development Alliance… in 2002, 2005, and 2009, we demonstrated that Hampton Roads is a highly interdependent economic region and the fruits of economic activity are broadly shared across the region.”

More than 65 percent of the people of Hampton Roads now leave their cities for work, an increase from the 61 percent measured as recently as 2009. More people from Virginia Beach work in Norfolk than people from Norfolk. Nearly 18,000 people from Chesapeake go to Virginia Beach to work.

The ODU economists cite the example of a hypothetical new distribution warehouse in Suffolk providing 250 jobs. Of those, on average, 30 workers would commute from Chesapeake. Twenty of the 250 jobs would be filled by people from Portsmouth; about the same number of workers would come from Virginia Beach. A dozen folks from Norfolk would work at the warehouse.

That kind of geographic interconnectedness is a fact of modern life in Hampton Roads. It’s why tolls at the Elizabeth River are so disruptive, for example, and why parochialism by politicians is so self-defeating and ultimately damaging to the region’s long-term interests.

Atomizing the region’s economic efforts – acting as 17 competing municipalities instead of one cohesive Hampton Roads – literally makes us smaller as a community. And as a force in the global economy.

“Market size affects the ability of firms to realize economies of scale in production and supply,” the economists wrote, and “shapes the extent to which highly valued specialty workers and products can be supported, permits the realization of agglomeration effects such that a critical mass of firms and workers arises and begins to act as a magnet.”

That’s what Hampton Roads needs to be. But the only way this region will become that magnet is if its constituent cities start acting in concert, on economic development and on so much more.